Classical Music and Brain Power

Listening to classical music, such as works by Mozart, has been shown to have a positive effect on focus and concentration. Some studies ha

Talking with ChatGPT about the 777 Hz Solfeggio Frequency

777Hz Solfeggio frequency promotes positivity & clears negative thoughts for a peaceful mind. Use it in meditation, yoga or daily activities

ADHD Relief Music - increase focus/concentration/ memory - Binaural Beats

ADHD Relief Music - Increase Focus / Concentration / Memory - Binaural Beats - Focus Music | 14 Hz Binaural Beats Mental Focus / Clarity

What the new ChatGPT says about binaural and polyrythmic beats

What the new openAI ChatGPT says about Polyrythmic and Binaural Beats

Music | Positive Energy Binaural Beats 777Hz and the Science of Solfeggio Frequencies

777 Hz + 432 Hz Attract Positivity, Luck, Abundance: Reprogram your Mind for Success - Binaural Beats Finalized Thesis statement: Sound...

Classical Relaxation Mix | Ambient Chill Remix

Created with Logic Pro X and this tutorial:

Binaural Beats and Calming Music - What are they and how you can make them in Logic Pro X

Binaural beats (or binaural tones or binaural shift) are auditory processing artifacts, or apparent sounds, the perception of which...

ADHD Binaural Beats - Best Focus Music for Natural ADHD Relief

ADHD Relief Music - Increase Focus / Concentration / Memory - Binaural Beats - Focus Music Get your ADHD Clothing:...

ADHD Relief Music: Poly-rhythmic Focus Music for Concentration

ADHD relief music with poly-rhythmic movement. Use this focus music during studying or other daily tasks. ~

Deep Focus Music: ADHD Relief Music for Better Concentration, Study Music

Deep Focus Music: ADHD Relief Music for Better Concentration, Study Music ~ My other channels: Sub Bass Meditation Music ►...

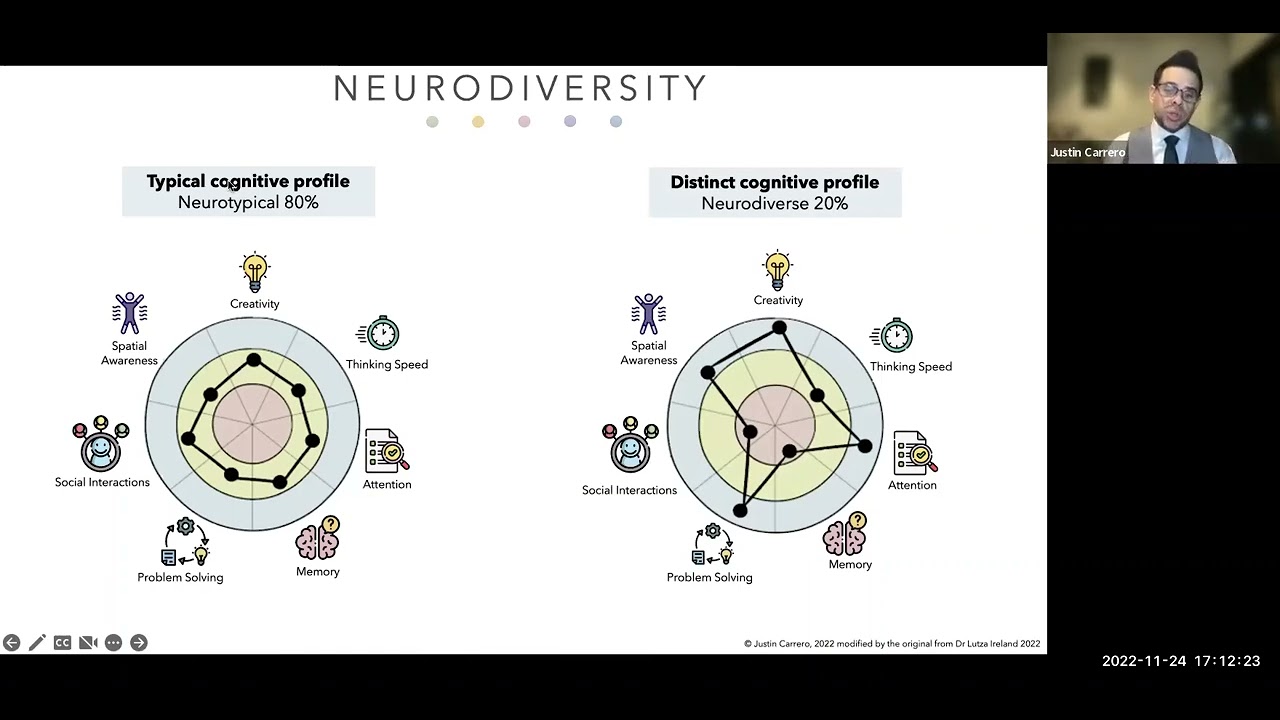

![Neurodiversity and Leadership in the Hiring Process [draft]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/0a19fd_a3299cad5f2041349ac65e30de6ead87~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_333,h_250,fp_0.50_0.50,q_35,blur_30,enc_avif,quality_auto/0a19fd_a3299cad5f2041349ac65e30de6ead87~mv2.webp)

![Neurodiversity and Leadership in the Hiring Process [draft]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/0a19fd_a3299cad5f2041349ac65e30de6ead87~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_300,h_225,fp_0.50_0.50,q_95,enc_avif,quality_auto/0a19fd_a3299cad5f2041349ac65e30de6ead87~mv2.webp)